How long do you want to live?

And if you should survive to a hundred and five

Look at all you'll derive out of bein' alive

And here is the best part, you have a head start

If you are among the very young at heart

Photo by Sabine van Erp/Pixabay

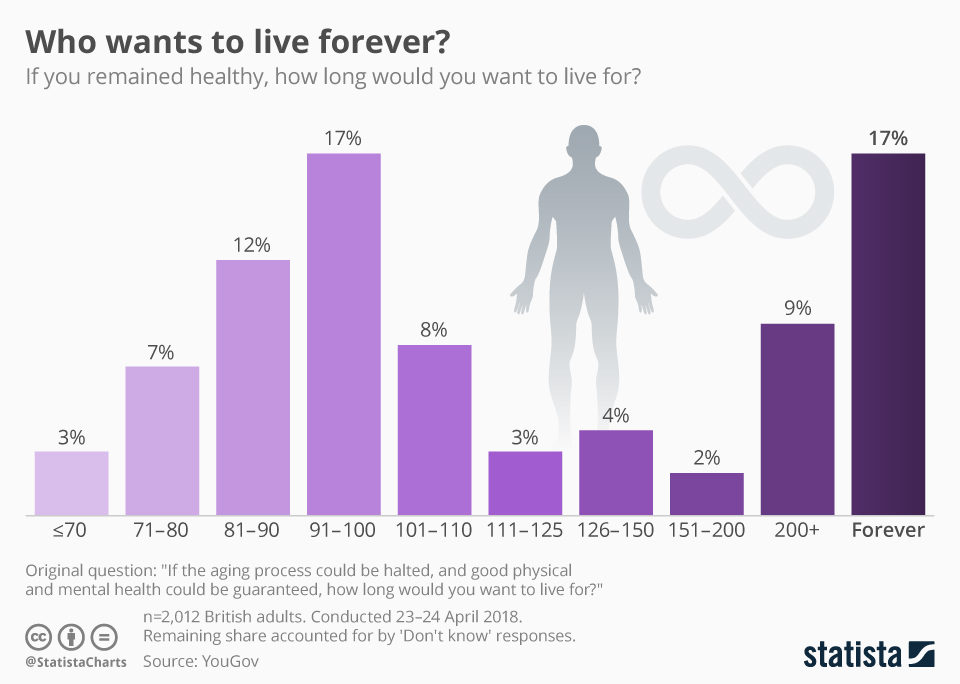

If you remained healthy, how long would you want to live? A 2018 study in Britain found that an equal number of people (17%) responded “91-100 years” or “forever”. In 2021, Steven Johnson published a book titled “Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer” that explores the extraordinary change in the human lifespan that has occurred in the last few centuries. Since pre-history, the average human lifespan from birth was about 35 years. A lot of that can be explained by the challenges of surviving childhood. For example, in the 1600s, when systematic information about births and deaths began to be recorded, about 12% of children did not survive the first year and 36% died before they were 6 years old. These sad statistics were true regardless of income or social standing, affecting rich and poor alike.

However, life expectancy began to improve beginning in 1800 and since 1900 the global average life expectancy from birth has more than doubled to 70 years. What is responsible for the change? Johnson describes three types of innovations. First, advances that saved millions of people, including anesthesia and treatments for AIDS and heart disease. Second, advances that saved hundreds of millions of lives, such as antibiotics and pasteurization. In the third group are the three innovations that had the largest impact, saving billions of lives: artificial fertilizers that improved crop yields so we can feed people, hygienic plumbing to prevent the spread of illnesses, and vaccines that promote immunity to diseases. Johnson emphasizes that most of these changes occurred as the result of small incremental steps, advances in basic science, and gradual implementation.

As a result of these changes, an “epidemiological transition” in the causes of death occurred. Instead of dying from communicable diseases in childhood, people lived long enough to develop chronic illnesses such as cancer or heart disease. The rate of infant mortality dropped to 3% in 2015, and only 4% of children died before they were 5 years old. Even though the advancements Johnson reviews benefitted everyone, not everyone benefitted equally. Before the epidemiological transition, communicable diseases affected rich and poor alike. After the transition, social class differences in health and lifespan began to appear. People with more education and higher incomes can have average life expectancies 10 to 15 years longer than the less fortunate in the same city or country. Moreover, average life expectancies for the world’s wealthier nations can be as much as 30 years longer than in the world’s poorer nations. The recent COVID-19 pandemic only served to highlight the relationship between wealth and healthcare.

In his review of the technological and healthcare advances of recent centuries, Johnson concludes that average life expectancy may continue to increase, perhaps to 160 years. Tech moguls in Silicon Valley have been working on just that question. With support from venture capitalists, the United States National Academy of Medicine created the Grand Challenge in Healthy Longevity providing millions of dollars in funding for breakthroughs to transform the way we age. The goal of the SENS Research Foundation in California is to cure and prevent the diseases and disabilities of aging. SENS stands for Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence – in other words, applying science and technology to minimize and delay the aging process. Although some scientists in these projects may want to “make death optional” or “undo” aging, for most the aim is to create the opportunity to live longer well – to ensure more quality of life in later years. One challenge of any therapies or technologies researchers in this area develop, is to ensure equal access and distribution. Development of expensive remedies that are only available to the very rich will only aggravate existing health inequalities.

Research on longevity and “extra life” returns us to the original question: If the aging process could be halted, and good physical and mental health could be guaranteed, how long would you want to live?

Source: https://www.statista.com/chart/15408/who-wants-to-live-forever-uk/

Detta är en bloggtext. Det är skribenten som står för åsikterna som förs fram i texten, inte Jönköping University.